Others have defended the EMH as being unfairly maligned. Jeremy Siegel, for example, argues that the EMH actually doesn't imply anything about prices being right, and insists that, recent dramatic evidence to the contrary, "our economy is inherently more stable" than it was before -- precisely because of modern financial engineering and the wondrous ability of markets to aggregate information into prices. Robert Lucas asserted much the same thing in The Economist, as did Alan Greenspan in the Financial Times. Lucas asserted his view (equivalent to the EMH) that the market really does know best:

The main lesson we should take away from the EMH for policy making purposes is the futility of trying to deal with crises and recessions by finding central bankers and regulators who can identify and puncture bubbles. If these people exist, we will not be able to afford them.

That debate over the EMH persists half century after it was first stated seems to reflect tremendous confusion and disagreement over what the hypothesis actually asserts. As Andrew Lo and Doyne Farmer noted in a paper from a decade ago, it's not actually a well-defined hypothesis that would permit clear and objective testing:

One of the reasons for this state of affairs is the fact that the EMH, by itself, is not a well posed and empirically refutable hypothesis. To make it operational, one must specify additional structure: e.g., investors’ preferences, information structure, etc. But then a test of the EMH becomes a test of several auxiliary hypotheses as well, and a rejection of such a joint hypothesis tells us little about which aspect of the joint hypothesis is inconsistent with the data.

So what does the EMH assert?

In trying to bring some order to the topic, one useful technique is to identify distinct forms of the hypothesis reflecting different shades of meaning frequently in use. This was originally done in 1970 by Eugene Fama, who introduced a "weak" form, a "semi-strong" form and a "strong" form of the hypothesis. Considering these in turn is useful, and helps to expose a rhetorical trick -- a simple bait and switch -- that defenders of the EMH (such as those mentioned above) often use. One version of the EMH makes an interesting claim -- that markets always work very efficiently (and rapidly) in bringing information to bear on prices which therefore take on accurate values. This (as we'll see below) is clearly false. Another version makes the uninteresting and uncontroversial claim that markets are hard to predict. The rhetorical trick is to mix these two in argument and to defend the interesting one by giving evidence for the uninteresting one. In his Economist article, for example, Lucas cites as evidence for information efficiency the fact that markets are hard to predict, when these are very much not the same thing.

Let's look at this in a little more detail. The Weak form of the EMH merely asserts that asset prices fluctuate in a random way so that there's no information in past prices which can be used to predict future prices. As it is, even this weak form appears to be definitively false if it is taken to apply to all asset prices. In their 1999 book A Non-random Walk Down Wall St, Andrew Lo and Craig MacKinley documented a host of predictable patterns in the movements of stocks and other assets. Many of these patterns disappeared after being discovered -- presumably because some market agents began trading on these strategies -- but there existence for a short time proves that markets have some predictability.

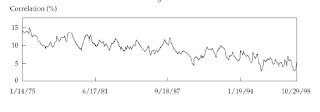

Other studies document the same thing in other ways. The simplest argument for the randomness of market movements is that any patterns that exist should be exploited by market participants to make profits. The trading they do should act to remove these patterns. Is this true? Take a look at Figure 1 below, taken from a paper from 2008 by Doyne Farmer and John Geanakoplos. Back in the 1970s, Farmer and others at a financial firm called The Prediction Company identified numerous market signals they could use to try to predict market movements in the future. The figure shows the correlation between one such trading signal and market prices two weeks in advance, calculated from data over a 23 year period. In 1975, this correlation was as high as 15%, and it was still persisting at a level of roughly 5% as of 2008. This signal -- I don't know what it is, as it is a proprietary signal of The Prediction Company -- has long been giving reliable advance information on market movements.

One might try to argue that this data shows that the pattern is indeed gradually being wiped out, but this is hardly anything like the rapid or "nearly instantaneous" action generally supposed by efficient market enthusiasts. Indeed, there's not much reason to think this pattern will be entirely wiped out for another 50 years.

This persisting memory in price movements can also be analyzed more systematically. Physicist Jean-Philippe Bouchaud and colleagues from the hedge fund Capital Fund management have explored the subtle nature of how new market orders arrive in the market and initiate trades. A market order is a request by an investor to either buy or sell a certain volume of an asset. In the view of the EMH, these orders should arrive in markets at random, driven by the randomness of arriving news. If one piece of news is positive for some stock, influencing someone to place a market buy order, there's no reason to expect that the next piece of news is therefore more likely also to be positive and to trigger another. So there shouldn't be any observed correlation in the times when buy or sell orders enter the market. But there is.

What Bouchaud and colleagues found (originally in 2003, but improved on since then) is that the arrivals of these order are correlated and remain so over very long times -- even over months. This means that the sequence of buy or sell market orders isn't at all just a random signal, but is highly predictable. As Bouchaud writes in a recent and beautifully written review: "Conditional on observing a buy trade now, one can predict with a rate of success a few percent above 1/2 that the sign of the 10,000th trade from now (corresponding to a few days of trading) will be again positive."

Hardly the complete unpredictability claimed by EMH enthusiasts. To look at just one more piece of evidence -- from a very long list of possibilities -- we might take an example discussed recently by Gavyn Davies in the Financial Times. He refers to a study by Andrew Haldane of the Bank of England. As Davies writes,

Andy Haldane conducts the following experiment. He estimates the results of an investment strategy in US equities which is based entirely on the past direction of the stockmarket. If the market rises in the period just ended, the strategy buys stocks for the next period, and vice versa. In other words, the strategy simply extrapolates the recent trend in the market. The result? According to Andy, if you had been wise enough to start this procedure with $1 in 1880, you would have consistently shifted in and out of stocks at the right times, and you would now possess over $50,000. Not bad for a strategy which could have been designed in a kindergarten.

Next, Andy tries an alternative strategy based on value. This calculates whether the stockmarket is fundamentally over or undervalued, and buys the market only when value gives a positive signal. The criterion for measuring value is the dividend discount model, first devised by Robert Shiller. If you had been clever enough to devise this measure of value investing in 1880, and had invested $1 at the time, the procedure would have left you with a portfolio now worth the princely sum of 11 cents.

That, according to the weak version of the EMH, shouldn't be possible.

If weakened still further you might salvage some form of the weak hypothesis by saying that "most or many asset prices are difficult to predict," which seems to be true. We might call this the Absurdly Weak form of the EMH, and it seems ridiculous to form such a puffed-up "hypothesis" at all. Does anyone doubt that markets are hard to predict?

But the more serious point with regard to the weak (or absurdly weak) forms of the EMH is that the word "efficient" really has no business being present at all. This word seems to go back to a famous paper by Paul Samuelson, the originator (along with Eugene Fama) of the EMH, who established that prices should fluctuate randomly and be impossible to predict in a market that is "informationally efficient," i.e. in which participants bring all possible information to bear in trying to anticipate the future. If such efficient information processing goes on in the market, then prices will fluctuate randomly. Informational efficiency is what Lucas and others claim the market does, and they take the difficulty of predicting markets as evidence. But it is not, in fact, evidence of anything of the sort.

Think carefully about this. The statement that information efficiency implies random price movements in no way implies the opposite -- that random price movements imply that information is being processed efficiently, although many people seem to want to draw this conclusion. Just suppose (to illustrate the point) that investors in some market make their decisions to buy and sell by flipping coins. Their actions would bring absolutely no information into the market, yet prices would fluctuate randomly and the market would be hard to predict. It would be far better and more honest to call the weak form of the EMH the Random Market Hypothesis or the Market Unpredictability Hypothesis. It is strictly speaking false, as we just noted, although still a useful, crude first approximation. It's about as true as it is to say that water doesn't flow uphill. Yes, mostly, but then, ordinary waves do it at the seaside every day.

So the weak version of the EMH isn't very useful. Perhaps it has some value in dissuading casual investors from thinking it ought to be easy to beat the market, but it's more metaphor than science.

Next up is the "semi-strong" version of the EMH. This asserts that the prices of stocks or other assets (in the market under consideration) reflect all publicly available information, so these assets have the correct values in view of this information.That is, investors quickly pounce on any new information that becomes public, buy or sell accordingly, and the supply and demand in the market works its wonders so prices take their fundamental values (instantaneously, it is often said, or at least very quickly). This version has one big advantage already over the weak form of the EMH -- it actually makes an assertion about information, and so might plausibly say something about the efficiency with which the market absorbs and processes information. However, there are many vague terms here. What do we mean precisely by "public"? How quickly are the prices supposed to reflect the new information? Minutes? Days? Weeks? This isn't specified.

Notice that a hypothesis formulated this way -- as a positive statement that a market always behaves in a certain way -- cannot possibly ever be proven. Evidence that a market works this way today doesn't mean it will tomorrow or did yesterday. Asserting that the hypothesis is true is asserting the truth of an infinite number of propositions -- efficiency for all stocks, for example, and all information at all times. No finite amount of evidence goes any distance whatsoever toward establishing this infinite set of propositions. The only thing that can be tested is whether it is sometimes -- possibly often or even frequently -- demonstrably false that a market is efficient in this sense.

This observation puts into a context an enormous body of studies which purport to give "evidence for" the EMH, going back to Fama's 1970 review. What they all mean is "evidence consistent with" the EMH, but not in any sense "evidence for." In science, you test hypotheses by trying to prove they are wrong, not right, and the most useful hypotheses are those that turn out hardest to find any evidence against. This is very much not the case for the semi-strong EMH.

If markets move quickly to absorb new information, then they should settle down and remain inert in the absence of new information. This seems to be very much not the case. Nearly two decades ago, a classic economic study by Lawrence Summers and others found that of the 50 largest single-day price movements since World War II, most happened on days when there was no significant news, and that news in general seemed to account for only about a third of the overall variance in stock returns. A similar study more recently (2002) found much the same thing: "Many large stock price changes have no events associated with them."

But if we leave aside the most dramatic market events, what about price movements over short times during a single day? Here too the evidence rather strongly contradicts the semi-strong EMH. Bouchaud and his colleagues at Capital Fund Management recently used data for high-frequency trading to test the alleged EMH link between news and price movements far more precisely. Their idea was to study possible links between sudden jumps in the prices of stock prices and possible news items appearing in electronic news feeds, which might, for example, announce new information about a company. Without entering into the technical points, they found that most sudden price jumps took place without any conceivably causal news arriving on the feeds. To be sure, the news entering did cause price movements in many cases, but most large movements happened in the absence of such news.

Finally, we can immediately also dismiss -- with the evidence just cited -- the strong version of the EMH which claims that markets rapidly reflect not only all public information, but all private information as well. In such a market insider trading would be impossible, because insider information gives no one an advantage. If I'm a government regulator about to issue a drilling permit to Exxon for a wildly lucrative new oil field, even my personal knowledge won't permit be to profit by buying Exxon stock in advance of announcing my decision. The market, in effect, can read my mind and tell the future. This is clearly ridiculous.

So it appears that the two stronger versions of the EMH -- which make real claims about how the markets process information -- are demonstrably (or obviously ) false. The weak version is also falsified by masses of data -- there are patterns in the market which can be used to make profits. People are doing it all the time.

The one statement close to the EMH which does have empirical support is that market movements are very difficult to predict because prices do move in a highly erratic, essentially random fashion. Markets sometimes and perhaps even frequently process new information fairly quickly and that information gets reflected in prices. But frequently they do not. And frequently markets move even though there appears to be no new information at all -- as if they simply have rich internal dynamics driven by the expectations, fears and hopes of market participants.

All in all, the EMH then doesn't tell us much. Perhaps Emanuel Dermin, a former physicist who has worked on Wall St. as a "quant" for many years, puts it best: you shouldn't take the thing too seriously, he suggests, but only take it to assert that "it's #$&^ing difficult or well-nigh impossible to systematically predict what's going to happen next." But this, of course, has nothing at all to do with "efficiency." Many economists, lured by the desire to prove some kind of efficiency for markets, have gone a lot further, absurdly so, even trying to make a strength of its own ignorance about markets, indeed enshrining its ignorance as if it were a final infallible theory. Dermin again:

The EMH was a kind of jiu-jitsu response on the part of economists to turn weakness into strength. "I can't figure out how things work, so I'll make that a principle."In this sense, on the other hand, I have to admit that the word "efficient" fits here after all. Maybe the word is meant to apply to "hypothesis" rather than "markets." Measured for its ability to wrap up a universe of market complexity and rich dynamic possibilities in a sentence or two, giving the illusion of complete and final understanding on which no improvement can be made, the efficient markets hypothesis is indeed remarkably efficient.

No comments:

Post a Comment